In the case of Nottingham, an almost identically sized city as Malmö, its current problems are acute and illustrative of wider failings in urban development. Nottingham is a big economy – generating by far the largest amount of per capita wealth in the East Midlands. Yet it has the lowest household income of any UK town or city.

If anything portrays the parlous state of late capitalism, this is it: a city that generates huge amounts of cash money – almost £9 billion a year – and yet very little of it goes to the people who actually live there. Nottingham has the youngest population of any large UK city, yet also has the lowest proportion of graduates who choose to remain after finishing their studies. It has one of the lowest proportions of school pupils who progress onwards to higher education and, like many other cities across the UK, US and Europe, has more than its fair share of precarious ‘bullshit’ jobs, leading to lower than average wages and understandably dampened aspirations amongst young people.

Photo: Simon Bernacki

There are many, good (great) things about this city. And skateboarding is surely one of them. A walk from Forty Two skateshop through Hockley and the Lace Market into Sneinton will take you past bars, coffee shops, Montana streetwear and graffiti supplies, Mim clothing, Broadway arts cinema, and into a thicket of DIY rehearsal spaces, studios and gig venues like JT Soar and Stuck on a Name. The sound of Nottingham’s skate scene has long rung far beyond its borders, with The Malibu Dog Bowl and the Hyson Green Bowls in the 1970s and 80s, to Kareem Campbell, Danny Way, Dill and Gino showing up at Old Market Square and Broadmarsh Banks in the 90s, and now the thriving community at Sneinton Market and the Nottingham DIY skate scene today.

Sneinton life. Photo: Michael McHugh

To link these assets and help address the challenges above, we did four things with our Big Lottery grant. We brought a bunch of boards and helmets, all from independent, UK-based companies (“Hi” to Landscape, Isle, Drawing Boards and Death) that would appeal to different tastes but were consistent with the values we wanted to support – and engaged beginners from the very start with deep skate culture and beautiful graphics, rather than retaining learners in an arbitrary quarantine in which only cheesy learner set-ups are good enough. Skateboarding is cool as hell, and everyone is cool enough to skateboard.

Myke Trowbridge – no comply, Sneinton Market. Photo: Charleigh Evison

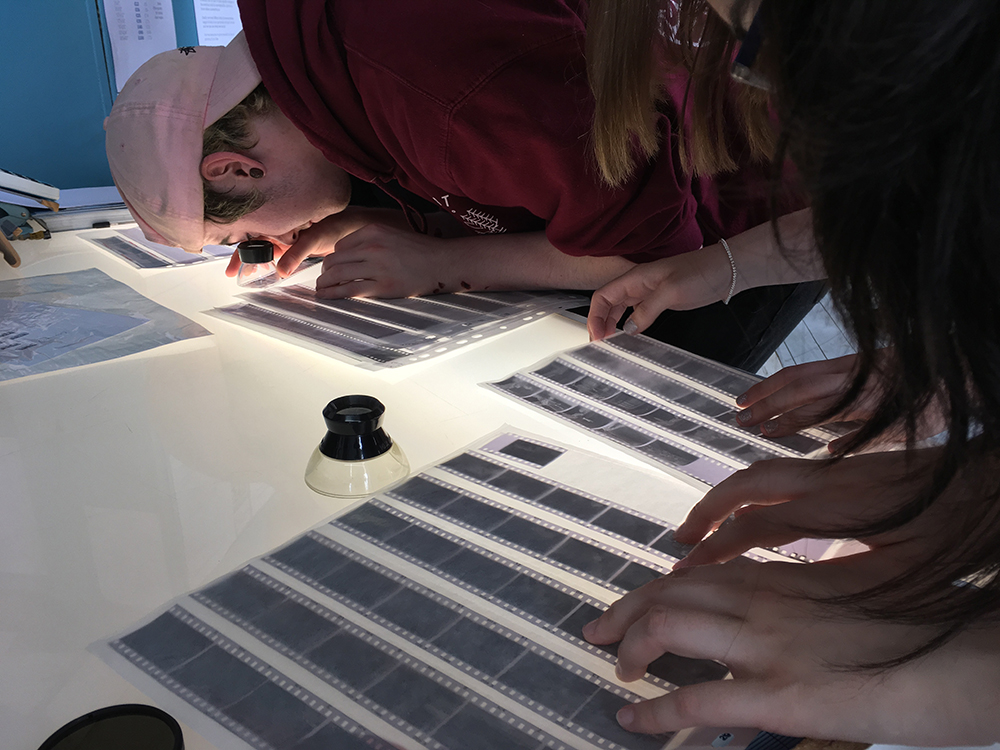

We invested in formal and informal training for skate coaches, not just so they could lead fun sessions safely, but so they are then equipped for careers in youth services or sport development – rather than the precarious, low pay warehousing and bar work so many skaters spend their 20s and 30s doing. We held back resource to run two terms worth of skate sessions, free to learners but where the coaches would all be paid at least the Living Wage – because their skills and time is valuable and it’s about time it was treated as such. And, as the cherry on top, we designed and delivered a workshop and exhibition that tried to build on the creative interests of young skateboarders, linking them to the development of specific, industry-relevant skills. This was inspired by the fact that, like many cities, Nottingham has a ‘creative quarter’ in which good jobs are concentrated, but jobs that only seem accessible to people with the right connections, qualifications and (often expensive) equipment. That Nottingham’s creative quarter is less than 5 minutes’ walk away from both Sneinton Market and one of the most deprived wards in the UK, St Ann’s, illustrates the invisible barriers that exist in most of our cities.

Photo: Simon Bernacki