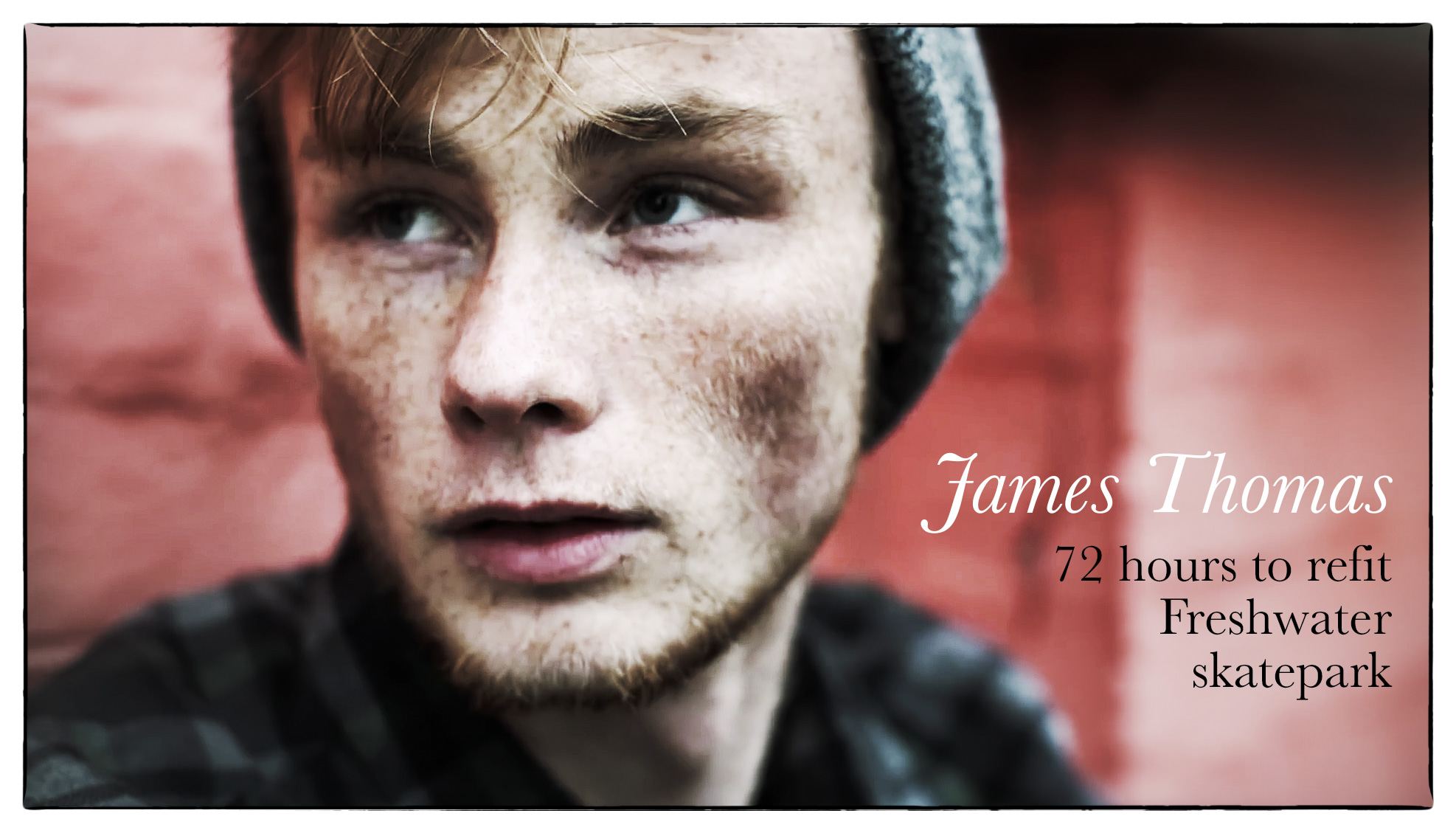

James Thomas – Freshwater refit

Isle of Wight local and budding skatepark designer James Thomas recently found himself with the opportunity to revamp his local Freshwater skatepark courtesy of the Channel US project.

The only obstacle in his path was that the project was limited to 72 hours – with the whole process, from designing the revamp, to physically building it, to holding an official re-opening jam having to take place in only 3 days. We caught up with James recently to find out how he dealt with the stresses of a 3-day timeframe, working with Channel US, and upgrading the park that he spent his youth at.

Your personal connection with the Freshwater park is pretty strong – am I right in thinking that you actually started skating when you moved to the Isle of Wight?

Yeah, I started actually skating a few weeks after I moved to the island, I already had a board that my parents bought me when I was knee high to a grasshopper, but it didn’t leave the house until I moved to the Isle of Wight.

You mentioned that the Freshwater park was ‘extremely close’ to where you lived – how close are we talking exactly – could you see it from your house?

The park was super close! Close enough that I could literally hear people skating the park from my bedroom window. I found this came in handy because after it rained I knew when the park was dry enough to skate again before everyone else, (laughs). I was like the local weather forecaster.

So you basically lived at Freshwater from the age of 14 then? How often would you be there?

As I said, I started skating when I moved to the Isle of Wight aged 14 and have been skating for just over 5 years now. I basically started because I moved literally across the road from the park so it was a no-brainer really. For about 3 years it was practically my home: I skated from when I got home from school to when it got too dark pretty much every day; needless to say, my GSCE results suffered because of this but what can you do? (Laughs), then I started A-levels and didn’t skate quite as much but still loved the park and the people who use it.

So it’s safe to say that this project to revamp the park was very close to your heart then?

Absolutely, I would say that I met 3 or 4 of my closest friends at that park and it became our space pretty quickly as there always seemed like an infinite amount of things to talk about, whether it was debating who had the best part in Stay Gold, (Westgate of course) or real world issues like the Ebola crisis. I learnt all of my basics there. Like literally all of them: first ollie, kickflip, varial flip, tre flip, shuv-it, 50 50s, rock fakie – I learned it all at Freshwater.

You mentioned that you’d spend hours on the Skate 3 game ‘designing skateparks’ when it was wet outside – what did you learn from that and how did that translate into what you ended up doing with this Channel US project?

The main thing I got from the Skate 3 game was actually an idea of aesthetics. The way a park looks and feels is just as important as how it skates in my opinion. In terms of how it helped me with the Channel US project, it wasn’t too directly related as most of things I’ve learned about flow have come from personal experiences of skating parks, from talking to the people at Maverick skateparks and through trial and error in my A-level coursework.

You aim to pursue a career in skatepark design/construction too, right? Can you tell us a little bit about that and whether it influenced your choice of University course please?

I wouldn’t say that it influenced where I decided to go to Uni as I live off my instinct, and the minute I came into Brighton for my interview I knew this is where I wanted to be; (possibly swayed ever so slightly by The Level being close to my campus). The actual course I do, I chose so that I could learn the basic universal principles involved in designing anything – like drawing to scale, using CAD properly, and learning how to make artistic renders on Photoshop. All skills that I believe will help sell my designs in the future.

You were in contact with the people at Maverick skateparks too, sending ideas over and trying to get a feel for the design process etc – how did it come about?

Maverick were so helpful. I actually originally sent them an email when I just turned 15, explaining about my ambitions, and I’d attached pictures of a skatepark I’d made on Skate 3. Obviously they told me straight away that no one in the industry would take me seriously if I was going to display my designs in that format but that helped, it gave me that little push I needed to start really making shit happen. So I did an entire A-level project on designing a skatepark and emailed Maverick probably once a week for around year with different questions, about health and safety, concrete types/thicknesses, skatepark life-expectancy, successful designs, not so successful ones, costings for labour and materials and many other things which people tend to forget about when skating a perfectly formed skatepark.

So through this connection with Maverick you were pointed towards a Camp Rubicon promoted opportunity to ‘redevelop your local skatepark’ – as somebody living on a tiny island community resources such as skateparks must be extremely important to the local kids, perhaps more so than to skaters living in large urban areas who have multiple places to skate and lots of skateparks nearby. Is this why you pursued this particular opportunity?

Yes, I was tagged in a comment on Rubicon’s Facebook post, which is how I came to see it initially. As you say, coming from somewhere like the Isle of Wight I was aware of how little there is to do for young people and thus how important places like Freshwater are. The skatepark really is the central hub for socialising for so many people on the island. It’s a genuinely key part of the youth community. I have such a tie to this park on a personal level too and so I really just wanted to give back to a place that shaped my entire life.

Channel US contacted you directly as a result of you getting involved with the Camp Rubicon competition – were you prepared for how much work you were letting yourself in for?

Yeah after leaving my comment suggesting why my local park should get the revamp, I was contacted directly by Channel US. I had a rough idea of how much work was needed to go into a project like this, but as everyone knows there are always going to be hiccups on the way that no one could foresee.

Designing skateparks on a computer is obviously very different from the reality of power saws and all the nuts and bolts stuff – which aspects of the process ended up being more difficult that you’d anticipated and why?

Andy (Willis) and his team did pretty much all the hands-on work as I was filming with Channel US for a large portion of the time that the build was happening. But the main issue I found was the time constraints. To get all the work done in such a short amount of time was quite a challenge.

It must’ve helped to have people with so much experience (John Cattle, Andy Willis, etc) involved too – what things did their experience bring to the table and how did you incorporate their wisdom into the process?

Massively! Andy and his team are amazing at what they do, and they’re all genuinely nice guys. Having someone on site knowing exactly what they were doing, and with previous experience of similar projects was so amazing. I already knew John (Cattle), he’s been a good friend for a few years now and I recently did an edit for his shop. I can’t give these guys high enough praise to be honest: and it was especially nice to have the support of Wight Trash via Cattle. In my opinion, experience is everything so having these guys helping made the whole project a lot of manageable.

72 hours is a pretty quick turnaround. I’m assuming that the design/plans were at least partly set out before you leapt into the 3 day process of physically upgrading Freshwater: as in – you kind of knew exactly what you needed to do build-wise.

Yeah we knew more or less exactly how the park was going to look. Andy and the team had already cut out the majority of the frames for the ramps, however it turned out that the ground of the skatepark want actually level so a lot of re-jigging had to be done at the 11th hour, which is where I think most of the timing problems occurred as it wasn’t something we’d planned for. This caused countless issues, with the designs of the framework of the ramps having to be adjusted to factor the uneven ground in, but we prevailed in the end.

How close to the wire were you? Was it a case of, “it’s finished – the jam starts in 5 minutes”?

Maybe not quite 5 minutes, but only a couple of hours before. Andy, Rodney and JP were down the park on the Friday before the comp until 11:30pm working via torchlight and using car headlights to illuminate the layout. Then we were back down the park for the final touches around 9am the next morning just in time for the opening jam. So yeah, pretty close to the wire stuff!

Looking at the whole adventure from today’s perspective – are you personally happy with what you achieved? What kind of feedback have you had from the local community and the people who use the park on a day-to-day basis?

The experience as a whole was pretty sick, I learned a lot within a short space of time, which I don’t think I could have learnt otherwise. Talking to my friends back on the island who use the park, the changes have definitely been well received. The park appears to be busier now as well, which is always massively encouraging.

What have learned from your involvement in this that you could pass on to anyone else wanting to undertake a similar project?

Be ready for the stress and embrace it. Everything else, just take it in your stride. Stressing out doesn’t help at all – just try to stay focused on the job at hand.