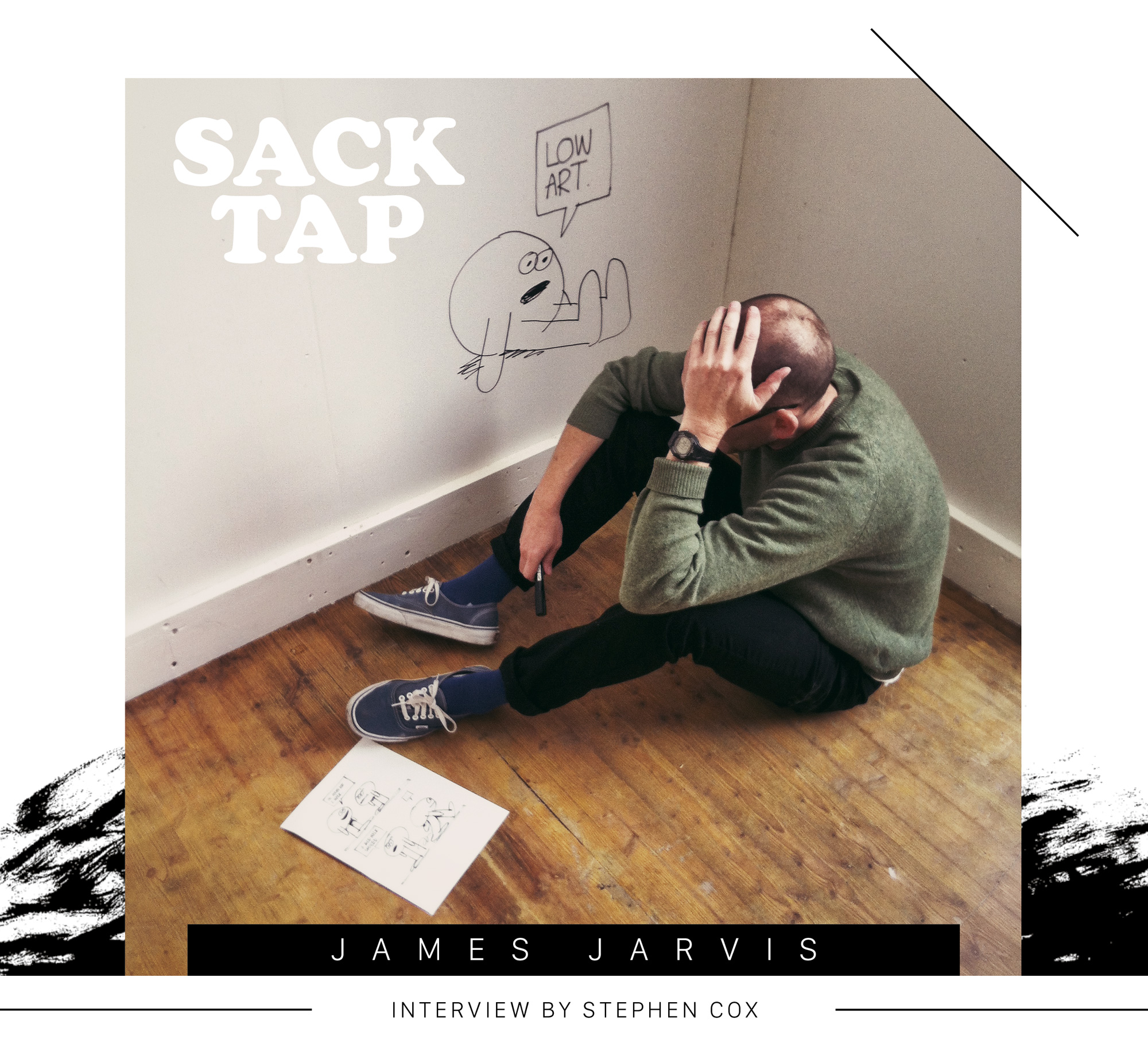

Sidewalk 223 – James Jarvis

If you're reading this it's likely that you enjoy, and even love skateboarding. Whether it's an old Slam City advert, a shop t-shirt or a board graphic, there's a great chance you've seen the touch of James Jarvis in some way on the very culture that you love. That's because James Jarvis loves skateboarding too. Just like you. Being both a genuine skate-nerd and artist will always provide for interesting conversation, especially when you throw in some philosophy for good measure. Drop into some negative space, geek out and listen to Jarvis speak about hoping his name was written down by the Gonz, making toys and barely-popped ollies.

Hi James how are things?

Not too bad, the kids have gone to bed. Normally I’m in my pyjamas, pretty tragic. But now is the time for lurking on the Internet and catching up with what’s going on the skating world.

You get caught up on the forum too during the day like the rest of us too surely?

A little bit in the day but I tend to watch videos more.

So tell us about your recent solo exhibition in Tokyo. Where does the phrase, “No More Negative Space” come from and what does it mean? I’m not sure if calling it a theme would be the right word but I’m interested to hear your take on it.

I don’t normally draw to a theme. The exhibition is a collection of drawings. That’s what I do all the time – draw. I don’t really think, “I’m going to draw this, or that”. I just draw stuff. When the guys in Tokyo asked me what I wanted to call the exhibition, there was a drawing that I’d called No More Negative Space. It was based on Ben Raybourn dropping in a vertical wall in Thrasher’s King of the Road.

I saw that.

It’s not really my cup of tea but there was that clip where he got all four wheels down on a completely vertical wall without any transition. I really liked that because on a philosophical level he was making use of space that you wouldn’t think could be skated. I just liked that idea, trick, drop-in or whatever it is. The thing I took from him and the drawing was that there was no space that could not be used in some way.

I was surprised to see the exhibition kicked off with some live paintings.

When I was in Tokyo I went around with the artist Haroshi, who makes sculptures out of old skateboards. He took me to some proper obscure street spots. I was drawing at those spots and I used those drawings to make a really big painting with spray cans. I’ve never used spray paint before so it was me kind of trying to experiment but with 350 people watching.

It made me think about how it is standard to see music and acting live but not drawing or painting.

I think generally drawings or painting are an internal process. One of my ideas is that there is no mystique to drawing; it’s a series of gestures and is a physical process of dragging some kind of material against a surface. Sometimes it’s like I’ve rehearsed the drawings and I know the movements so well that I can make them whenever I need to. So to do them in public is less of a leap. I was almost working as I would in my studio but in public really. Live painting just has a catchy ring to it.

You seem to be very adamant about what drawing is and means to you. As you’ve mentioned you seem to place an emphasis on the physical act of drawing. Where does this come from? Is it a continuation from drawing for so long? How did you arrive at this sort of thinking?

It’s a mixture of things. When I was younger I just drew because I enjoyed it and was driven to do it. I ended up studying it because I wanted to make a living out of it and then started thinking more consciously about it. Then after about 10 years from I when I started making work professionally after college or when I turned pro – I like to think of it in terms of skateboarding – I started to think about what it was that I was doing. One of the things I realised was that I got very involved with making toys and computer-based graphics, which are quite constructed and not that connected with hand-drawing, which was the thing I started off doing. I became conscious that I’d moved away from drawing and it got me thinking about what I’d lost and wanted to get back again. That turned into an effort of getting everything back to by-hand again. When I was at college there was one computer, which you had to book to use for an hour but obviously now it’s different. Back then I embraced it without really thinking about what it meant, because it was new. Maybe after 10 years of getting involved with computers you suddenly think about what it has done to your work and how it has changed your approach. I’ve been through the experience of understanding what computers can do but now there’s what it can’t do. I had to get back to the human touch really.

Was AMOS an unexpected turn in your life? Do you think there could be a similar great change in direction for you in the future?

I don’t really think about it but I’m conscious I’ve moved away from Silas/Amos. I had a [career] trajectory. I did some ads for Slam City in the mid-90s and they started a clothing company called Holmes. I did some drawings for that then the guys who did that left to do their own thing which was Silas and the first thing they did for Silas was make that toy. That took on a life on of its own and led me into making toys and starting a company, which was something I never planned to do. It was exciting at first but once you know what you’re doing, you start doing things on autopilot and it stops being adventurous. I think where I am now is a very different stage of life; I’m a middle-aged bloke with two kids. I’m not living the same kind of life I did when I started. I’m entranced by this idea of making things in a really basic way and a rediscovery of drawing. I’m not really looking beyond that because I feel like I haven’t quite finished working out what I can do with it.

I saw the Nike SB edit in which you said artwork was your ‘in’ to skating. Did you mean that in terms of it becoming a hobby or in a working capacity?

I think they’re two separate things in a way. There’s skateboarding and there’s wanting to be involved with it in an industry way. My in to skateboarding was skateboarding but my in to skateboarding in a professional capacity was drawing. I saw the copy of Thrasher when I was 12 and I just thought it was the coolest thing ever. That happened separately to the art thing and obviously I was more driven to do that. The thing about skating was that I never had a skate crew. I started skating more heavily when I went to Brighton for art school where I had more space to do it. My parents didn’t understand my interest in skateboarding, which is funny because they were incredibly supportive of me being an artist and had no qualms about me going to art school but they didn’t get why I liked skateboarding. They just thought it was for kids. I say to my mum now how it’s funny that she didn’t get it and it’s the thing that I built a career around. In a way I look back and wish I had spent more time skateboarding but instead I was drawing in my room listening to music. I didn’t have that confidence to go out. There weren’t that many people doing it in the early 80s, or at least I didn’t know that many people doing it. I didn’t know kids at the end of the street. It was more that I decided to go out and be a skateboarder.

In terms of the drawing then did you find it intimidating going into the skate shops and speaking to the older generations to become involved?

I was just into it and had my friend in Brighton. We used to go out and skate all the time, every evening. We were crap but we just loved it. I was looking at all the World Industries graphics around 1991 thinking it was just the best. I just loved what Sean Cliver and Marc McKee were doing. I wanted to have a similar role I suppose. I think I might have faxed Slam some work and they asked if I could bring some more in when I was next in London. So I went into Slam when they were doing Insane – Ged Wells’ company – which I was super into. I loved those graphics. I thought maybe they’d like what I was doing. I showed them my work and they thought it was cool and told me to stay in touch. Then a while after I moved back to London to do my MA at the Royal College of Art I went into Slam again and Andy Holmes recognised me and I showed him a little book I made about skateboarding. He said, “This is wicked, go and show it to Sofi [Prantera] and Russell [Waterman] they’re starting a new clothing company”, which was Holmes. I felt like I was winging it but I was so into it that I was prepared to do it. I was 23 or 24 so I wasn’t super young. I can see a 16 year old being intimidated, but a 24 year old? That was the culture of it though. It was an unforgiving subculture.

How essential are skate shops like Slam?

The shop is a weird cynical creature, which is a good thing because it brings you back down to earth. It’s a place where you go and can’t stand on ceremony because everyone knows where you’ve come from, you can’t bullshit and I think that’s a healthy thing. I went into Slam to do this artist talk and I do know a lot of the guys but I don’t hang out there regularly. I suppose when I went in I felt like people were too respectful because I’m of an older generation, so no one is going to go, “You know what? That was fu*kin nonsense what you were just saying!” But I would want them to because if anybody should or could it would be that community. That’s what I like: skateboarders are not afraid to say what they think about something.

The Krooked graphic looks great. How long did it take to come up with? How did it all start up?

Thanks. It was just, “do you want to do an artist board?” “Yes”.

[Laughs].

I was probably the most legit thing I’ve been asked to do as an artist in skateboarding. I’m enough of a skate nerd to know what Deluxe and Krooked represent so to be asked to do that was quite exciting. I had that traditional nursery rhyme in my head straight away: there was a crooked man who walked a crooked mile. I wanted to do something that had a concept and had content to it. It was pretty straightforward. I wanted to use the stripped back, basic drawing that I’m using these days. Unfortunately I don’t think the Gonz had anything to do with it, which would have been really exciting. I was looking on the Krooked website to try and work out if it was the Gonz who does the actual handwriting on the catalogues: “Did the Gonz write James Jarvis? That would be wicked”.

It’s better not to know then.

It is better not to know [laughs]. They also want me to film a little edit. I said, “OK but you can’t film me skating”. But that’s what is nice about skating; it’s a real community of people. You tend to find that connection. It’s like that Kevin Bacon thing, you’re never more one person away from knowing somebody else. So you kind of trust people in a way where working with big companies or advertising is totally different. I kind of like that. I know that Deluxe isn’t going to fuck around with what I’m doing because it’s just not what we do. I think people don’t do that sort of thing for the money. I find it way more thrilling than making a toy. Seeing your work on a skateboard. But I hate the idea of wall hangers.

You do?

Yeah. The idea of making boards to be wall hangers.

Ah right. I get you.

I really liked doing the last set of graphics I did for Heroin because they were team graphics. The Descent and Krooked stuff is great. I met someone in Japan and they had a really thrashed Descent board and it’s brilliant. It’s the best thing ever because they bought it for all the right reasons. It’s really gratifying. You also can’t ride your own board graphics. It’s like pros riding their own boards.

Surely you’ll hang the Krooked one though?

No I don’t really hang anything. I don’t really hoard. I think it’s 8.25 so I think it’ll be too big for my kids. I’ve a big stash in the basement. I’ll lean it against the wall and look at it for a bit.

[Laughs]. Who is doing things right in terms of skateboarding-related drawings in the UK currently? Are you inspired by anyone in that way?

It’s nice because – maybe through Instagram actually – I’ve got to know a younger generation of artists: Bromley, Kyle Platts, Jack Sachs. I’m kind of envious because I wish I had had that kind of community when I was younger. I’m inspired by these people and I love what Blast is doing with their company. But aside from that I do try and work in a vacuum. I used to get that weird insecurity with other people doing good work too but now I just get stoked on seeing people do things and be proactive. There’s a guy who did some guest graphics for Isle called Lee [Marshall], he’s a favourite.

Putting aside aesthetics, are you inspired by the philosophies of others too? Is that possible?

That was the thing that made this transition of wanting to draw again. Maybe a bit of a middle-aged existential crisis going on there. I did a whole project about philosophy for myself. I spent a lot of time trying to understand philosophical concepts, trying to work out how it could fit in to what I was doing. I suppose that idea of drawing as a tool for understanding the world came as much from skateboarding as it did from philosophy. I got to thinking about what was good about skateboarding. The thing I liked wasn’t the hammers or technical progression, it was more the philosophical idea that skateboarding exists as a very unique pursuit. What makes it special is the way it almost is a philosophy. What I’ve got is more elemental and what makes me good is maybe that philosophical level. So I decided that instead of trying to make drawings that look good, I would make drawings that were truthful and hopefully the honesty would be the aesthetic. Obviously I do think about aesthetics but I try not to let that drive what I’m doing. I was doing a talk at Slam to launch this trainer and I was trying to draw some parallels and I said, “It’s like Anthony Pappalardo not wanting to skate like he did when he was on the Workshop”. He wanted to bring it back to the basics and I really understand why he would want to do that. If it’s been done there’s no point in doing it again.

Just before I called I was watching his commentary of his i.e part.

People get so upset by him: “He’s super negative”. I understand though. You always tend to see the faults and not the great bits. You don’t want to look back. It takes a few years to accept things for what they are and he’s still a young guy. When I look back I think things look awful. People get stoked on different facets of what you do though and they want you to go back because they like something you did, which is fair enough.

What’s keeping you interested in UK skating at the moment? Where are things headed? Is everything on the up and up?

I prefer the companies that have a kind of philosophy, the ones that have something they want to say about skateboarding. I really like Polar. I like Magenta; I like their philosophy. I was reading that discussion about Glen Fox. It was really cracking me up; people get so angry [laughs]. I like their philosophical approach and the way they conceptualise skateboarding. There are lots of companies that do that. Some I like art-wise, some I don’t but I admire them all. Plus everyone is killing it these days. Tom Knox is fuckin’ amazing. I really love watching Dave Mackey skate. I’m there going, “ah, my knee is too fucked. I can’t ollie that crisp packet” and Mackey is skating with that style. You know that boring cliché, ‘it really doesn’t matter what you do it’s the way you do it’ – that’s the truth. I’ve enjoyed watching Brian Lotti skate recently. He skates like an old guy, not in a restricted way but just that he doesn’t want to skate like a hyperactive kid. There’s a slowness to the way he skates that is amazing. I was watching some Chris Pulman clips recently and he just still has that style. When there’s a concept it gets me excited. I loved that Glen Fox thing, I don’t care if his ollies aren’t massively popped. I haven’t seen anyone else do that in that way. When there’s something you haven’t seen before and someone thinks about things in a different way, that’s what gets me stoked. But yeah, as far as I’m concerned everybody is killing it. I want everybody to stop saying ‘killing it’ though. We need to find another way to say that.

[Laughs]. Can you throw out some advice to those that want to pursue their drawing?

Keep doing it. I think the problem with skateboarding and drawing is that if you really want to be good at something you have to do it to the exclusion of everything else. I think the reason it worked for me is that I completely devoted myself to it. It’s a calling rather than a lifestyle. You’ve got to love it.